Sustainable Development Goal #2 is to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture

Within SDG #2 are eight targets, of which this episode will focus on Target 2.1:

By 2030, end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round.

SDG #2 flowing on from SDG #1 implies the obvious interrelationship between poverty and hunger, with the poor most sensitive to fluctuations of food prices.

Target 2.1 flows on from target 1.C of the Millenium Development Goals, which was to “halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger.”

This target was met, but left 795 million people undernourished, including 90 million children under the age of 5.

Within target 2.1 are two indicators:

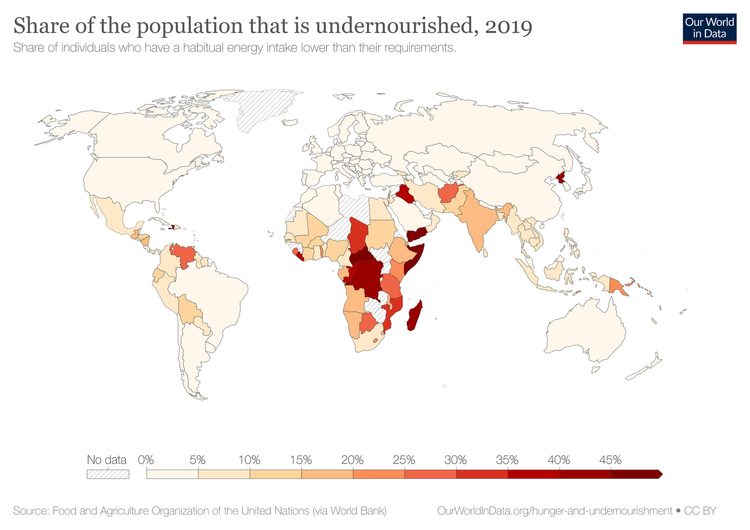

Indicator 2.1.1: Prevalence of undernourishment.

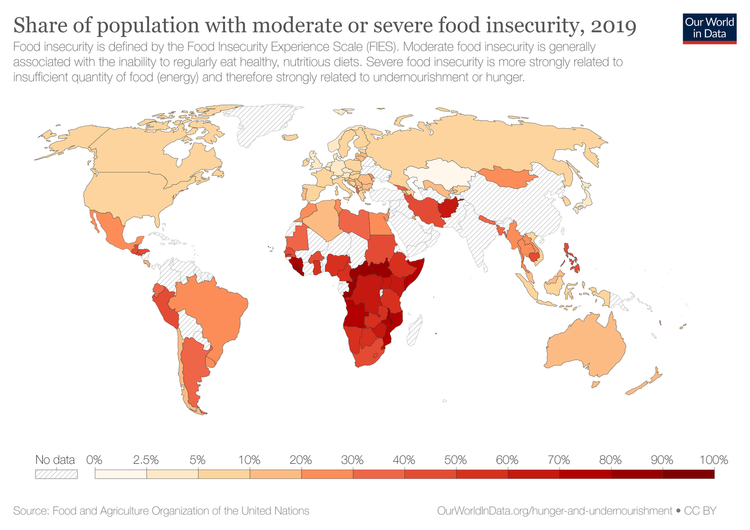

Indicator 2.1.2: Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the population, based on the Food Insecurity Experience Scale.

Hunger, in the context of sustainable development, is obviously differentiated from the sensation of being less than satiated. In the context we’re looking at, it is the global leading cause of death. It is to be unable to meet the essential nutrients humans require to sustain healthful lives over a long period of time.

Dismayingly, the global areas most vulnerable to acute hunger are those experiencing wars, pandemics and extreme weather.

Looking closer at the concept of undernourishment underpinning Indicator 2.1.1, undernourishment is a diet with insufficient nutrients. By this we mean calories providing us energy, but also the right biochemical combination to allow for proper metabolism, in the form of proteins, carbohydrates, fat, vitamins and minerals. Tragically, at the most extreme end of undernourishment is starvation.

Also worthy of mention is the more specific instance of micronutrient deficiency, whereby an individual is experiencing undernourishment of a particular vitamin or mineral necessary for healthy functioning.

Target 2.1 specifically mentions infants, as nutrition during pregnancy can affect the gestating baby for life, highlighting also the importance of breastfeeding for newborn’s nutrition.

Many of us are familiar with the heart-rending images of starving children displaying the hallmarks of malnutrition in the poorest parts of the world. The medical term, marasmus, is often characterised by the wasted mass of emaciation for overall energy deficiency. For children no longer nursing with the proteins of breast milk, and have instead moved to a diet of starchy carbohydrates with little other nutritional value, we recognise the symptom of distended abdomens, caused by swelling of fluid retention and a liver overwhelmed with fatty deposits. This condition, termed kwashiorkor, is caused by sufficient calories, but protein deficiency. In the following target, we’ll also look at the high prevalence of stunting, caused by undernutrition.

In subsequent SDG #2 targets, we’ll also look at the role of agriculture, particularly sustainable agriculture, to feed a global population approaching a trajectory of 9-10 billion without abutting the planetary boundaries, as well as the systems for which food is produced and distributed.

Despite the prevalence of malnutrition as described being overwhelmingly associated with the developing world, some developing countries are beginning to see another form of malnutrition far more common in the developed world: the inverse of undernourishment - overnutrition, overeating and obesity.

Development aid, from the developed countries to the developing world, is a clear remedy to preventing and reducing undernourishment in the form of dietary supplements, food fortification to enrich foods with micronutrients, and other forms of food aid.

Aid is also required for developing countries to provide medical care for those in critically ill conditions requiring intensive care for undernourishment, perhaps compounded by an infectious disease.

Furthermore, aid can assist the development of sanitation systems to ensure drinking water and sewage do not mix, which can lead to infectious diseases causing undernourishment. This can again be compounded by undernourishment leading to dehydration, further exacerbated if the drinking water isn’t sanitary, and contaminated by infectious pathogens.

To meet the definition of undernourishment for the purposes of Indicator 2.1.1, using household surveys, we’re looking at regularly not having access to food sufficient to provide the energy for a normal, healthy and active life, given their own dietary energy requirement.

Often due to the geographical isolation, hunger acutely affects the most vulnerable regions of the world, represented by the UN’s list of least developed countries, landlocked developing countries, and small island developing countries.

Food insecurity, the focus of Indicator 2.1.2, is the ability of households and individuals to access food. It measures the percentage of individuals in the population who have experienced food insecurity at moderate or severe levels in the period of the SDGs. It’s measurement tool, the Food Insecurity Experience Scale, is a survey of 8 questions.

With the aim by 2030 to achieve zero hunger as part of SDG #2, as of 2020, a tenth of the global population, equivalent to 811 million, experienced hunger and was undernourished. Tragically, the World Food Program, the food aid branch of the UN, has estimated that due to the effects of COVID-19, the number of people suffering acute hunger may have doubled by the end of 2020. COVID-19 may also have pushed between 83 and 132 million into chronic hunger.

Though the trend of hunger experienced globally had been steadily decreasing, since 2015, when the SDGs were adopted, the UN’s agency focused on alleviating hunger and ensuring food security, named the Food and Agriculture Organisation, or FAO, has identified the total number of those living in a state of hunger has risen, predominantly in Africa and South America, with the main culprits being climate, conflict and recessions.

An estimated 2 billion people, or a quarter of the global population, experienced moderate or severe food insecurity in 2019, up several percent since 2015. Much of the increase came from Latin America and the Caribbean, though the largest numbers remained in sub-Saharan Africa.